“It is not sufficient to know an artist’s works.

It is also necessary to know when he did them,

why, how, under what circumstances.”

Pablo Picasso

Panorama is undoubtedly a monumental project. In style and content, it represents a logical continuation and a radical departure, an entirely new challenge and the culmination of the artist’s work to date. Designed to fit inside the Flaschenturm [Bottle-tower], one of the two surviving defensive towers of Altenburg Castle, it contains 45 views of the towns and landscapes of Thuringia around its 20-metre circumference. Rather than following the form of a traditional 19th Century panorama (such as the Panorama Mesdag in The Hague), which adopts a single, if illusory, vantage point from which to construct a continuous 180o or a 360o scene, Anthony Lowe’s Thuringian panorama encompasses an assortment of discontinuous perspectives, while the individual elements are flattened and contorted by the use of multiple viewpoints. To create these scenes, Lowe – although by inclination a thoroughly painterly artist – has turned to the computer, blending and manipulating photographic images to emulate the style of his painted works, kneading, twisting and stretching them like pizza dough. They are then enlarged or reduced to fit the continuum, before being printed onto panels which are joined to build the finished object. The result takes the artist’s work to a new level of ambition both in conception and in its impact on the viewer, while it blends 21st Century technology and sensibility with the aesthetics of 19th Century Realism.

Realism has always been fundamental to Lowe’s work. As a student at the Royal College of Art during the 1980s (when it was at the centre of a revival in English figurative art), he would make studies in the local butcher’s shop and later on brought a pig’s head back to the studio for use as a model, until fellow-students took matters – and the head – into their own hands, and threw out the foul-smelling Beelzebub. Perhaps on account of events such as this – certainly because he was starting to establish a unique, mature style as well as showing a dedication to his profession that contrasted with the dilettantism of many other students – Lowe left the Royal College with a reputation amongst his teachers for being ‘interesting.’ This reputation directly led to a commission in 1987 to paint the Transporter Bridge in Middlesbrough for a collection of contemporary art that was being formed by a local public gallery.

The bridge – one of only ten surviving in the world – is a notable example of engineering: it still carries vehicles and foot passengers across the River Tees after more than a century, and is the town’s great landmark and its pride. Lowe buckles the steel girders and contorts the river’s shores as though tectonic plates had shifted. Even so, the bridge stands firm, like some immense industrial staple holding the two banks together.

This experience perhaps was in his mind when, after arriving in Germany, he set out to paint Dresden’s Blaues Wunder [Blue Wonder], another steel bridge, and another monument to the skills of engineers from a century ago.

Blaues Wunder (1991) writhes across the Elbe, and the elegantly-rising girders of the original are distorted into gigantic mechanical saw-teeth. It is, of course, inevitable that a painter of cityscapes will depict bridges, and yet the symbolism cannot be ignored of the bridge as a structure that traverses barriers to unite two sides. In 1991, for his exhibition with Julian Perry, A Several World, Lowe offered as a statement: ‘My work is concerned with where things meet, where stone meets sky, water touches land and East meets West.’

Coming to the German Democratic Republic (as it then was), Lowe arrived in a place where East met West, although the bridges were few and fragile, and there was little by way of a meeting of minds. The Glienicke Bridge, between West Berlin and Potsdam, became famous for exchanges of spies, while Checkpoint Charlie (now the site of a museum) and the other crossing points in the city were fortified and guarded. At this distance in time and space, when Germany is just another European partner and Berlin a tourist venue, it is hard truly to recall the Cold War world.

For Britons in the 1980s, the GDR, like the rest of the Eastern bloc, was a faraway country of which they knew little: they were aware of it mainly as a backdrop to the novels of Len Deighton and John le Carré. The Iron Curtain was an architectural fixture; at the same time, having grown accustomed to the possibility of Mutually Assured Destruction, they viewed the GDR as somewhere that managed simultaneously to be mysterious and drab. For East Germans themselves, the old regime, with its guarantees of welfare and employment, has nowadays acquired something of a distant charm – they have coined the term Ostalgie [Nostalgia-for-the-East]: then, while they were living through it, there was a partly-idealistic yearning for reunification – for access to separated family members, for a single national identity, for greater freedom of choice, for escape from the all-pervasive Stasi and, not least, for access to the material goods so evident in the West. People were shot trying to escape. From time to time the border guards themselves were killed. All were seen as martyrs on one side or the other. In communist rhetoric, West Berlin was a stake driven into the heart of the GDR: in the western media it was represented as an outpost of the free world. West Berliners saw themselves as encircled by communism: conversely, East Berliners felt they were surrounded on three sides by the forces of capitalism.

For Britons in the 1980s, the GDR, like the rest of the Eastern bloc, was a faraway country of which they knew little: they were aware of it mainly as a backdrop to the novels of Len Deighton and John le Carré. The Iron Curtain was an architectural fixture; at the same time, having grown accustomed to the possibility of Mutually Assured Destruction, they viewed the GDR as somewhere that managed simultaneously to be mysterious and drab. For East Germans themselves, the old regime, with its guarantees of welfare and employment, has nowadays acquired something of a distant charm – they have coined the term Ostalgie [Nostalgia-for-the-East]: then, while they were living through it, there was a partly-idealistic yearning for reunification – for access to separated family members, for a single national identity, for greater freedom of choice, for escape from the all-pervasive Stasi and, not least, for access to the material goods so evident in the West. People were shot trying to escape. From time to time the border guards themselves were killed. All were seen as martyrs on one side or the other. In communist rhetoric, West Berlin was a stake driven into the heart of the GDR: in the western media it was represented as an outpost of the free world. West Berliners saw themselves as encircled by communism: conversely, East Berliners felt they were surrounded on three sides by the forces of capitalism.

This was the world into which Lowe was parachuted, thanks to the British Council’s scholarship exchange programme, for ten months in 1988.

Any interest in Eastern Europe was bound to be tinged by politics. 1980s Britain was dominated by Margaret Thatcher, whose government seemed set to last a thousand years; communism offered an image of equality (albeit equality of poverty), and, however stubborn and stupid individual regimes might be, there was a sense that they could one day be reformed into something close to a socialist ideal. For Lowe, however, there were more significant considerations. Since his time as a student he had admired the German Expressionist artists and art groups: Ludwig Kirchner (born in Chemnitz, renamed Karl-Marx-Stadt), and Max Beckmann (born in Leipzig); Die Brücke [The Bridge] (founded in Dresden and so-named to signify the links the artists felt to one another), and Der Blaue Reiter [The Blue Horseman]. The Expressionists distorted line, form, colour and compositional balance in order to convey emotions and sensations, subordinating their subject-matter to the expression of the artist’s psychological state. They borrowed elements of primitive and folk art, although their output was anything but naïve. It is easy to understand Lowe’s interest, and see echoes in his own practice. He is above all a portrait-painter of the urban environment: he reveals the personalities of the towns and cities he depicts, and, in equal measure, his responses to them. Human figures hardly feature in his work and – when they do – their features lack the power of the brick and stone that sprawl with simulated chaos across the canvases. Multiple perspectives and linear dislocations lead the viewer’s eye on a disorientating dance through the paintings, while the fantastic colours draw it in to scrutinise the details. The distortions form an invitation to re-examine familiar views and perhaps reawaken a forgotten sense of beauty, of amusement or of threat in them. It is hard to avoid comparison with the Expressionists, even though Lowe started from a very different point.

Then, in 1984, the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford mounted Tradition and Renewal, the first-ever exhibition of East German art in Britain. Lowe was entranced. It showed how the aesthetically-bankrupt Soviet style of Socialist Realism had been transformed into a vibrant form in which the inner world of the artist blended with the external perceptions of the viewer. Until now, his principal influences had been at the Royal College: Stephen Farthing, Peter de Francia, Graham Crowley. Suddenly, he was discovering Werner Tübke, Willi Sitte and, above all, Bernhard Heisig, the Head of Leipzig’s School of Visual Arts. He wanted to see and know more, and the British Council provided the opportunity.

Lowe arrived in Leipzig (speaking no German, at a time when the country’s second language was Russian, not English) and found studio space alongside a group of other artists in a building originally erected by the state to enable Tübke to create ‘the largest painting in the world’.

The Art School under Heisig, and – through its influence – the scene across the city, was dynamic and diverse: it was the powerhouse for fine art in the GDR; it was where the party was happening. The state was the major source of patronage for East German artists: once accepted into the Artists Union, they were guaranteed a number of commissions and hence a reasonable income. It was less concerned, however, about supporting a transient westerner, and from the outset Lowe was orientated towards private sales. Succeeding in a mixed economy was not, in fact, so difficult: the lack of luxury consumer goods in the East, plus security of accommodation and employment, meant that anybody with a little spare cash was likelier than in Britain to buy an original artwork for their wall. In addition, the gap between artists and the general public was far smaller than in the Britain of that time: an artist – like most other people – was (in part at least) a public employee, and artists paid to sketch a street scene were liable to have passers-by looking over their shoulders and telling them what they were doing wrong.

Lowe thrived, partly because – as an exotic alien, the only Englishman they were likely to meet – he was welcomed by a hospitable community, partly because he combined graft and sociability, partly through an innate strength of purpose. At the end of the exchange, he returned to England, where he became Painting Fellow at Cheltenham College of Art. But middle-class Cheltenham was a long way from Leipzig, and in 1990 (the scheme’s final year) the British Council awarded him a second scholarship, enabling him to return. And Leipzig, the city that was by then the epicentre of anti-government protest, became his home.

For most of 1989, nobody dared predict how the upheavals in Eastern Europe would turn out. In Budapest and Prague, East Germans were packing out West German embassies to seek right of passage across the more relaxed borders that new liberal communist regimes had established. In Berlin, however, hard-line Erich Honecker was still making speeches in support of Beijing’s clampdown in Tiananmen Square.

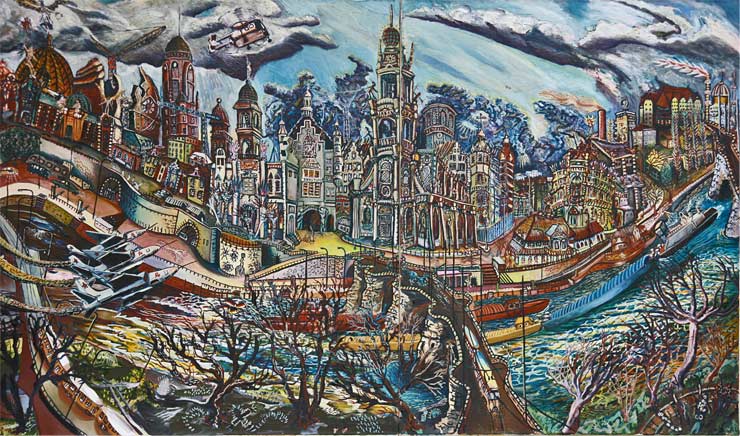

In1989, Lowe, painted Pushing through Dresden, a large canvas (1.4m x 2.5m). The following year, it so happened, he was commissioned to create an even larger painting (2.4m x 4.8m) of Hartlepool, in North East England, for the main staircase of the new Central Library there. By that time, he was on his way back to Leipzig, where the work was completed in 1991. Its title,

On the Beach, makes reference to Neville Shute’s novel of life following the dropping of an atomic bomb, although the two works span a period when, for the West at least, the threat of Armageddon miraculously receded. From an Eastern European perspective, however, the familiar status quo was ending, and it was hard to grasp what might replace it.

In the event, a cataclysm occurred – and yet, beyond it, life continued. Pushing through Dresden is painted as a panorama: the bend of the River Elbe has been reversed – as if Canaletto’s camera obscura had been fitted with a fish-eye lens – so that viewers are made to feel the canvas should be peeled from its stretcher and curved around them. In the centre, the Augustusbrücke (another bridge!) leads the eye across the river to the remaining buildings of the Altstadt [Old Town] that survived the British bombing and later demolitions. On the bridge itself, a blue horse (for a Blue Horseman?) has collapsed: perhaps a foretaste of the faltering regime. Russian fighter jets – symbols of the colonial power – scream across the sky, trailing vapour clouds, while a government helicopter keeps watch overhead. In the top left corner, a devil leaps to try and touch the sculpted angel that floats on outstretched wings above the dome of the art school.

The devil (it has to be said) is in the detail, when it comes to considering Lowe’s works. It is essential to get up close and explore the elements, rather than stand back to admire a harmonious overall effect. The artist deconstructs the cities that he paints, and the paintings themselves have to be approached in the same spirit.

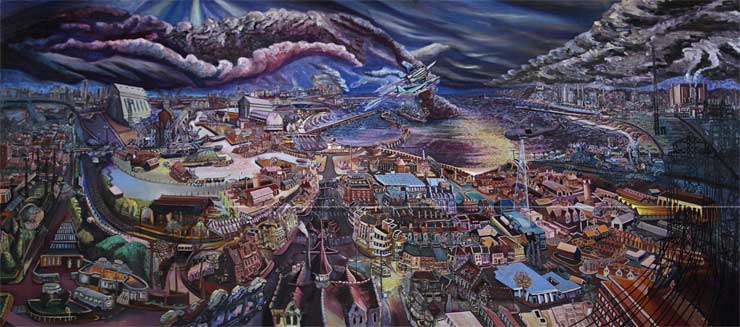

The Hartlepool painting shows an aerial view of Church Street running down to the beach. There are similar warplanes – only this time with American markings – soaring past the town, and on the right another helicopter with a searchlight pointing downwards to search for miscreants: a metaphor for the power of the state.

Unsurprisingly, there is less in the way of historic landmarks (after all, Dresden was once known as the Florence of the North: Hartlepool was not), but the purple cloudscape is worthy of some Olympian god descending from the black infinity beyond, or of a biblical Transfiguration scene. Lowe’s studies for the Dresden painting were carried out at ground level, and the elevated eyeline is a product of the artist’s imagination. His studies of Hartlepool were made from the tower of a disused church (now an art gallery) in the town centre: this led to a comic scene, where passers-by – assuming that the silhouette against the sky was a would-be suicide – shouted: ‘Don’t jump!’ and were given the answer: ‘It’s alright: I’m an artist!’ Artists, it is understood, float on angels’ wings.

In the GDR, Lowe was floating successfully, and generally able to exhibit a certain humour which is characteristic of his work. This was not so for the political regime, nor for one particular painting of the time.

Der Grosse Baum [The Great Tree] of 1990: the year in which the formal reunification of the two Germanys took place, following the opening of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. The tree of the title is the Fernsehturm [Television Tower] built in the 1960s as a landmark for East Berlin (taller than the Shard in London and visible for miles): but in the painting the tower has been uprooted, and the surrounding cityscape is devastated. There is a huge fire in the centre from which the buildings on either side recoil. In the bottom left corner are figures who seem to be trying to destroy a bridge (!).

Lowe’s works are frequently full of an anarchic energy, but this is perhaps the most dynamic of any: the splintered buildings splay in all directions, and the viewer can almost feel the ground shake from the impact of the fall. Both the palette and the loose brushwork in the picture’s foreground seem a conscious echo of the work of Bernhard Heisig, making the work an epitaph for GDR art as well as for the state. Other East German artists were creating works in a similar vein, some with titles like Colossus, showing the collapse of monumental figures or the rising up of new ones. It felt like a heroic time.

Artists – like everybody else in the former GDR – had to come to terms with losing the security previously provided by the state and facing a harsher, more competitive world. The new order produced winners, losers, and cynical exploiters of the situation. West Germans felt that they were subsidising the East; East Germans that they were being colonised by the West. The expression ‘Mauer im Kopf’ [the Wall inside the head] was widely used – and from time to time still is. One of the uglier outcomes of reunification was the spread of right-wing extremism across the former GDR: initially led by West German groups but quickly moving beyond their control. .

In a letter from that time, Lowe wrote:

‘Last night, I was so angry. Three little gits on the Strassebahn [tram], two with fluorescent baseball bats adorned with swastikas strutting around and shoving people. There’s absolutely nothing you can do: they’d tear you apart in seconds. It’s not as if these types haven’t already killed and crippled people in Leipzig…The week before saw an attack on a cafe in which eight people were seriously injured with baseball bats and shot in the face with air pistols. Meanwhile, the local paper carries interviews with shop owners saying how pleased they are to have the protection of the National Party groups…’

It could have been the rise of Hitler all over again. In 1991, he painted

Glatzkopfnacht [Night of the Skinheads]. The work is dominated by the sinister streetlamps which have shot up and blossomed like malevolent night-flowers. Their ice-green light falls on a meandering tram for which there are no passengers. The belligerent figures in the foreground – the last dregs of the human race – may perhaps be emerging from an underpass, but it looks rather as though graves are giving up their dead for the Final Judgement: a judgement that is bound to be inhuman.

In 1993, Lowe moved to Altenburg, where – ironically – he himself was beaten up by a similar gang of Neo-Nazi thugs: in a small town he was more readily identifiable as a foreigner, and foreigners were no longer welcome.

Altenburg is 50 km south of Leipzig as the crow flies but far further psychologically (one of Lowe’s views of it, from 2010 is Titeled Toy Town). It has a population of around 35,000, less than a tenth that of Leipzig, and most of its history occurred over three hundred years ago. It has its own, distinct cultural identity: this is in no sense second-rate, but it is unquestionably quirky.

The local museum has a priceless collection of Italian 13th – 15th Century art, and the town is known as the birthplace of Skat, a card-game widely popular in Germany but almost unknown to the rest of the world. It manufactures playing cards and mustard; it has its own independent brewery and – implausibly – the Apollo supercar works. Just as improbably, for some years, it had an airport with direct flights to London. Lowe’s decision to settle in Altenburg had little to do with any of these things, but it suited him at that moment in time, standing as he did a little apart from the mainstream of post-reunification art in Germany (he reckons there are 20 world-class artists currently practising in Leipzig). In Altenburg, he found a steady stream of clients – individuals and companies – who wanted views of the town or of places that they knew.

Over the following years, Lowe must have painted a hundred works for private clients: doctors, dentists, lawyers and the like. The owner of the mustard factory was a significant patron, as were local banks. Commissions also arrived from elsewhere (four works were bought by the state of Thuringia for its offices and public buildings), but Lowe became known as the Altenburg artist. He talks about the skill of painting to commission: of the need to listen to people describing what they want, and wrapping his own style around it. In between commissions, he made some adroit loans of unsold pieces, and painted others with an eye to sites where, while they were unlikely to be purchased, they could be a kind of poster for his abilities. Thus, while the airport was in use by Ryanair, a circular painting of London hung in the small departure lounge. In this, he was following in the steps of artists ever since the Renaissance.

In the later 1990s, Lowe’s work became more tranquil for a time. Much of the expressionist distortion disappeared, and the mixture of levity and angst was replaced by a sense of composure. This could to some degree be the outcome of the subject-matter he was addressing.

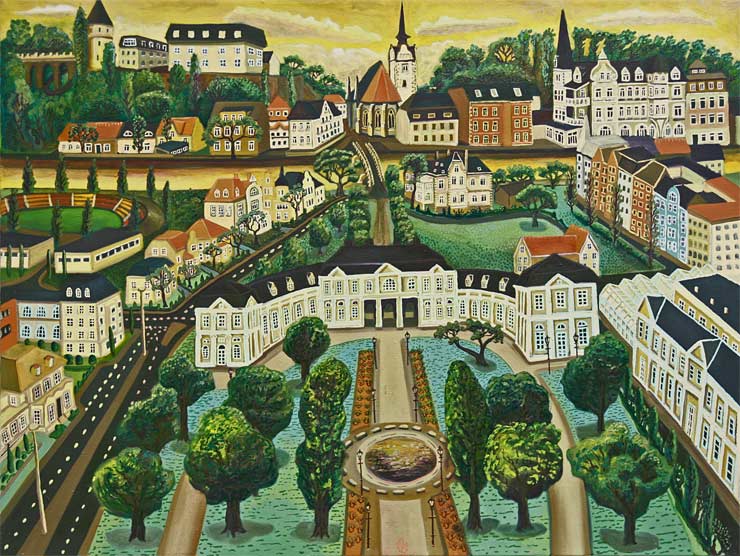

The Nymphenburg Palace (Nymphenburg, 1999) was the summer home of the royal house of Bavaria: its restrained opulence and the deathly symmetry of its architecture make it hard to imagine anything tumultuous occurring there – in fact, anything at all (in 1961, the Alain Resnais film L’Année dernière à Marienbad was shot there, a film that gave rise to the description: ‘Where nothing happens very slowly’. The location made an ideal backdrop). This is as orderly a work as Lowe is ever likely to paint, from the rooftops on the skyline to the white lines along the road.

This tidiness is echoed in Gera Orangerie (1999), another pleasure-garden, but the building itself houses Gera’s collection of art by its most famous son, Otto Dix, the antithesis of calm and beauty. Might not the work have dropped some hint of what was inside?

And what are we to make of München [Munich], 1999: surely the Bavarian capital must have more going on? Shorn of their dynamism, the folk-art element becomes more evident in these works. There are also signs of formulism: a ribbon – a road, a bridge, a waterway – runs almost vertically up the centre of the canvas to divide the scene in two. The compositions are nicely balanced, in contrast to the triumphant turmoil of the earlier works. Was Lowe becoming conventional? Was he – like so many artists of earlier centuries – on a production treadmill: a little too successful amid a steady flow of commissions to have the time to think too hard? In this context, a line from the artist quoted in a 1999 exhibition catalogue is illuminating:

‘I don’t mind if some people see my work as conservative. The pictures that I paint aren’t for gallery people, but primarily for the 99% who don’t deal professionally with images. I want to produce works that people understand (whether they like them, of course, is another matter). I could sit in libraries for months and come up with a highly philosophical subject, but only a handful of people might understand it. Everybody in the town can understand these.’

Anthony Lowe, Jäger im Dschungel der Stadt [Hunter in the Urban Jungle]

It is only fair to say that Lowe would undoubtedly be capable of coming up with philosophical subjects, if he so chose. Some might judge this statement as abandonment of the avant-garde and surrender to populism or commercialism. By contrast, it can be seen as keeping faith with the principles of art practice in the GDR, where the artist was a public servant, and the 99% of the population were entitled to look over his shoulder and tell him what he was doing wrong.

In 2000, Lowe moved from Altenburg to a small house in a village a few kilometres south, onto which he was able to build a studio: now, the first time, he had his own purpose-built atelier attached to his home. Coincidentally or not, his work became more idiosyncratic again; it regained its sense of playfulness and delight in distortion, but with fewer of the sinister undercurrents found in the works of the late 80s and early 90s.

The centrepiece of Leipzig (2007) is the city’s GDR-era university tower rising like the blade of a scimitar into the sky. But the sky is blue, the rain clouds are far off, the top half of the building is in sunlight (although, down below, the streetlamps are lit), and we sense that this is a celebration of a new age, not a premonition or the threat of an attack. Neither is there any hint of Ostalgie here.

In successive paintings of Altenburg, the town’s twin steeples grow impossibly tall and writhen; windows take the form of eyes or open mouths; turrets become cartoon ghosts in floppy hats. As any gallery education officer will affirm, children love spotting details in paintings, and while (as has already been said) all Lowe’s works need to be approached in this way, it is easy to imagine that these paintings in particular would be appreciated by younger viewers.

Toy Town, 2010, has a dalek, and Altenburg Landlos, [Landless Altenburg] 2011, a spaceman. Such details are seldom arbitrary, however, and more than merely whimsical. Lit streetlamps feature regularly in Lowe’s works: they carry echoes of the security lighting that ran along the eastern side of the Berlin Wall (where the lamp standards were orientated away from the footpath to illuminate the Wall itself and any would-be escapees).

In his earliest painting of Leipzig, a huge raptor hovers over the city, but it is a sparrow-hawk rather than a German eagle. His explanation for the dalek is that the Dr Who villains are the perfect embodiment of a fascistic regime. Spacemen, by contrast, represent for Lowe the best hope for humanity’s survival: he predicts the need for a second Colombian conquest of a new world, to solve the planet’s crises of population and food production. Talking about his current work, Lowe says: ‘The problems of the world aren’t found in my art.’ This is not strictly true, but they are maybe less insistent than before. Perhaps the problems seem more distanced: chronic, rather than acute. The artist is at the heart of his environment and no longer on the edge. And he continues to display a mixture of lightheartedness and gravity – he rejects the need to be one or the other – a British rather than Germanic trait.

In parallel with these works, Lowe was experimenting with another kind of panoramic presentation. In some of his cityscapes, foreground details had been inverted (as if the artist were leaning out of a hole in the floor of a helicopter).

His interior of the cathedral at Zwickau (Dom Zwickau, 2011) systematizes this: the work shows the four walls at different angles, as if the scene had been taken from high in the vaulted nave looking straight down at the rows of pews. Indeed, in theory, the canvas could be displayed horizontally on a plinth, to be viewed from all four sides. Lowe has developed an interest in M C Escher’s graphics, and the links with the latter’s works are obvious (see, for example, Hand with Reflecting Sphere and St Peter’s Rome, both from 1935). Lowe takes this a stage further in one of the prints that he made following a visit to New York.

The circular New York Apple, 2012, is a view of the city’s skyscrapers looking simultaneously up into the sky and downwards to the East River, while the buildings around the circumference are distorted as though the canvas is spinning: all calculated to induce vertigo. Escher’s influence is evident here, too, from his tessellating patterns to his dizzying viewpoints; and, in its way, the work is just as dynamic as the Grosse Baum that came crashing to the ground with the fall of the GDR.

The concept of the panorama is old: it originated in 18th Century Britain (Wordsworth wrote superciliously about one on show in London, for giving viewers the illusion that they were in touch with the sublime: how he would have hated television!). From Lowe’s 360o vistas and contorted scenes, it is easy to see where the artistic techniques of Panorama have originated. Equally, there are precedents in his work for the speculative gesture and the appeal to a broad public. There is logic in the Altenburg artist coming forward to offer his candidacy as an artist of Thuringia. What are quite new are the monumental scale and the use of computer technology. The opportunity gave rise to the first, and that in its turn necessitated the second. The Flaschenturm is hardly climate-controlled: oil on canvas would not last there. Industrial printing is more durable, besides being reproducible on demand, in whole or in part (Lowe sees the piece as a database for future print editions). The soundtrack, incorporating an original score by Falk Zenker, is a further departure that Lowe felt the work and the location demanded. This is not a modest experiment, and the artist raised the stakes by publicising his plans rather than keeping them concealed till he was certain of success. It has been a leap without a safety-net. But then, as has already been established, artists float on angels’ wings.

Mike Hill 2012 Hutton Rudby Yarn